2020: Triumph of the Optimists

I love sitting down to write my annual client letter – pulling out the nuggets from the last twelve months and weaving an interesting story is fun for me. And what a plethora of nuggets there are from 2020.

2019 was a great year – the S&P 500 returned (including dividends) 31.5% in 2019. We didn’t quite keep up with that in 2020 but it was (in purely investment terms) what I would call ‘quite a good year’. The S&P 500 finished the year (again, including dividends) up 18.4%. Isn’t that mad?

Whilst the US stock market was a clear out-performer, the majority of countries saw positive returns in their stock markets. The average return (according to Charlie Bilello) was 3.6%. The notable exception was the UK where the FTSE 100 had its worst year since the financial crisis, falling 11.8%.

The word “unprecedented” has been thrown around this year. But 2020 was not unprecedented (2021 on the other hand…). Years like this have happened before and they will happen again. 2020 was a year where we got to see the whole movie. It was a year that serves as a master class in the principles of successful long-term, goal-focused investing.

Before I remind you of those principles, let me break down the S&P 500’s 18.4% return and take a look at how we got there.

Many years ago, in my first job in Cayman I wrote a newsletter about how a return is a return, and it doesn’t matter how you get it. How wrong I was. The journey, as 2020 taught us, matters a great deal.

On February 19th of 2020 the US stock market started its fall. What then happened over the next 33 days was incredibly painful and stressful. The US market (defined by the S&P 500) fell 34%. Small stocks, emerging markets stocks, and European stocks fell further. Here is the only truly unprecedented part – the market had never fallen that fast before. The order of magnitude was not unusual (we can expect the market to fall a third roughly once every 4 years or so), but the speed was. 33 days was unprecedented.

Then, almost as fast as it fell, it recovered. By August 18th 2020 the S&P 500 was back at an all-time high. And from there it continued. From the bottom on March 23rd to today the market is up over 70%.

That’s how we got there.

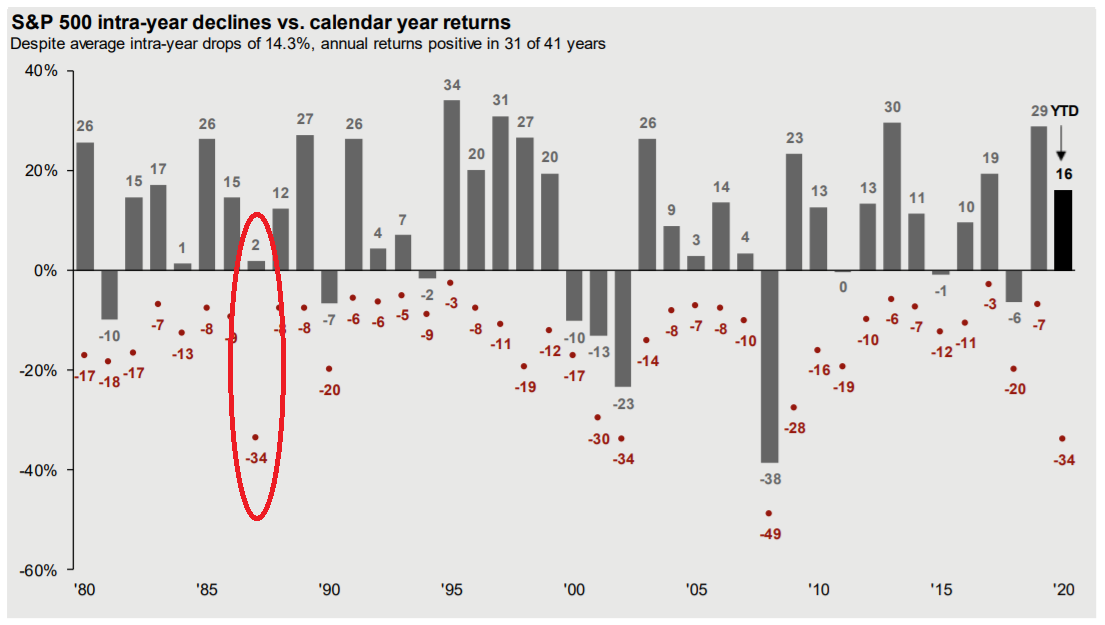

This is one of my favourite stock market charts:

Source: FactSet, Standard & Poor’s, J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Returns are based on price index only and do not include dividends. Intra-year drops refers to the largest market drops from a peak to a trough during the year. For illustrative purposes only. Returns shown are calendar year returns from 1980 to 2020, over which time period the average annual return was 9.0%.

Guide to the Markets – U.S. Data are as of December 31, 2020.

If you internalise and understand this chart, you know everything you need to know.

Please take a moment to read this.

The grey bar shows the annual return for each year, from 1980 to 2020. The red dot shows the intra-year decline for that year; that is the largest drop from any peak to any trough during that year. The return has been positive in 75% of the years and during this period the S&P 500 has gone from 106 to 3800. The average intra-year decline is 14.3%. So, to have turned 106 into 3800 you had to ride out a fall of over 14% on average every year. And then approximately every four years you had to ride out a fall twice that bad.

Historically when explaining this chart I have use 1987 as the example. It’s circled. (Now I have 2020).

This is what happened in 1987. The intra-year decline was 34% (as it was in 2020). The annual return from the end of 1986 to the end of 1987 was 2%. If you don’t know your market history, 1987 was the year of Black-Monday.

On October 19th 1987 the US stock market (the DJIA) fell 22.6%. 22.6% in one day. Can you imagine? Maybe you remember it?

The total fall around that Monday was 34%. However, 1987 was a positive year. I always say, if you had fallen asleep at the end of 1986 and woken up again at the end of 1987 and looked at your account statement you would have thought ‘mmmm…not much happened – I made a little. Not great, not terrible.’

During my adult years I have seen three major market crashes (dot-com collapse, Great Financial Crisis and COVID), but I can’t imagine the feeling of seeing your portfolio fall by almost a quarter in one day.

There are many similarities between 1987 and 2020. The difference is that if you had fallen asleep at the end of 2019 and woken up again at the end of 2020 and looked at your account statement, you would probably have concluded that a series of generally good things had happened during the year.

Not for a moment would you have concluded that the world entered the worst pandemic since 1918, that the US saw the largest quarterly economic contraction ever and the highest intra-year unemployment rate since the Great Depression.

What do we learn from all this?

Here are the lessons and principles, as they appear to me:

· The big events come far out of leftfield and they can never be predicted. Trying to make investment strategy out of “expert” prognostication will always set investors up to fail. Successful investing is always goal-focused and planning-driven.

· Market declines are a feature and not a bug, and they always end. Whilst the words ‘this time is different’ are uttered during every market decline, it’s never really different. Optimism is the only realism and optimists will always triumph in the long-run.

· The market cannot be consistently timed. Attempting to get out at the top and in again at the bottom is fool hardy. Given that the market goes up most of the time, the best day to get in was yesterday. The next best day is today.

· Stay the course is the most unsatisfactory piece of advice and yet simultaneously the only piece of advice that works. The only way to benefit from long-term permanent uptrend is to ride out all the temporary declines. Taken a step further, permanent loss in a well-diversified portfolio of the great companies of the world is always a human accomplishment and something the market itself is incapable of.

· The less you look at your investment account the happier you will be.

Where do we go from here?

I asked this question last year, and the year before.

I have no idea where the S&P 500 will be in a year’s time. I have no idea whether bond yields will go up or down. I don’t know whether Bitcoin will continue its meteoric rise.

But, I do know that out of crisis comes great opportunity and innovation. When we humans are forced to act, we act. Scientists save the world when scientists are forced to save the world.

The speed of technological change has accelerated dramatically in the past nine months. Packy McCormick wrote recently, ‘we haven’t just accelerated the adoption of tech, we’ve accelerated the acceleration’. We are creating a more dynamic, innovative and creative economy, the extent of which I don’t think can yet be understood.

When we emerge from this with herd immunity (either naturally or via the vaccine, hopefully the latter) and the economic and psychological impacts of the virus are behind us, to put it bluntly, humans are going to go wild. We are currently cooped up, saving money, being abstemious (as a whole, if not individually!). If history is a guide, we will enter a post-pandemic period where all the current trends are reversed. We will fill restaurants and bars again, we will travel again, concerts and sporting events will return. We will gather and roam like never before.

The case for a repeat of the roaring 20s is becoming stronger.

Some would argue that the headwind is valuations.

Here’s my take on valuations.

There is obvious excess (or madness) in various parts of the market.

To put the figures above into perspective, Cisco (which briefly became the world’s most valuable company) had a peak P/E ratio of 196x in March 2000. It fell almost 90% when the bubble burst and twenty years later it is not back to its high.

Big tech is almost certainly in a bubble (bubbles can go on for a long time) but what about the market as a whole? The S&P 500 is more expensive today than it was this time last year, when I said I wasn’t concerned about valuations. If you look at the cyclically-adjusted price to earnings ratio (so called CAPE – a popular metric used by market historians) we are at the second-highest level, behind only the dot-com bubble. On the face of it, this is not great.

However, “long-term” looks back to as early as the 1800s. I don’t believe you can compare the stock market in 1900, for example, to the stock market today.

This chart shows the industry weightings in the US and UK stock markets in 1900 and 2020.

Source: Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2020, Summary Edition

It actually is a different world today.

Should stocks not be worth more today than they used to be? In a recent blog post Michael Batnick pointed to low interest rates, low inflation, Fed intervention, fiscal policy or the way market structure affects market behaviour as just some of the reasons why they should.

I am not yet panicked about valuations for two main reasons.

Firstly, whilst large growth stocks are expensive (as shown above), the divergence between growth and value is at the highest since the dotcom bubble. Over the past few months we have started to see a resurgence in small companies and value stocks. Your diversified portfolio will benefit if this trend continues.

Secondly, you have exposure to the global stock market, not just the US. The S&P 500 has dominated the past ten years of performance. That won’t continue forever. Valuations of European and emerging markets stocks, whilst not cheap per se, are far from troubling. They look very attractive versus US stocks, as shown below.

Source: JP Morgan Guide to the Markets

It has never paid to bet against the US economy, US innovation or the US spirit. Despite the troubles of today (and I write the day after the ‘insurrection’), as your advisor, I do not recommend betting against the US over the coming decades. Owning US companies alongside the other great companies of the world and holding them for the long-term is the only strategy that will grow and sustain real wealth. Faith, patience and discipline – that’s all we have.

I want to finish with one observation. It may be the most important nugget in this letter, particularly if you feel like you are losing faith.

The dotcom bubble peaked in March 2000. If you had bought the S&P 500 that month and held to today your return over that 20-year period would have been 6.6% per annum (inclusive of dividends). What that means is if you had picked what you could argue was the worst entry point in history, but you had managed to hold on through the 2007 global financial crisis and the 2020 COVID crisis, you would have fared well.

And let me tell you, we are nowhere near the bubble of the dotcom era today.

Charles Bilello ended his 2020 review (which is well-worth a read) with the following words, which I cannot beat:

Weigh the evidence as it comes, invest based on probabilities, be forever humble and thankful, and leave the predictions to those whose job it is to entertain. That’s the best you can do in this fickle business of investing – try to find the right path for you and stick with it long enough to reap the enormous benefits of compounding.

Thank you all again for the trust you place in me every day. I never take this responsibility lightly. We got through 2020 successfully together – we can get through anything! Stay optimistic - this next decade is going to be a wonderful time to be alive.

My best, always

Georgie

georgie@libertywealth.ky